Resistant!

Equine parasites are becoming resistant to our de-worming compounds. This blog post addresses why this is a HUGE CONCERN not only for your horse, but for the entire horse industry.

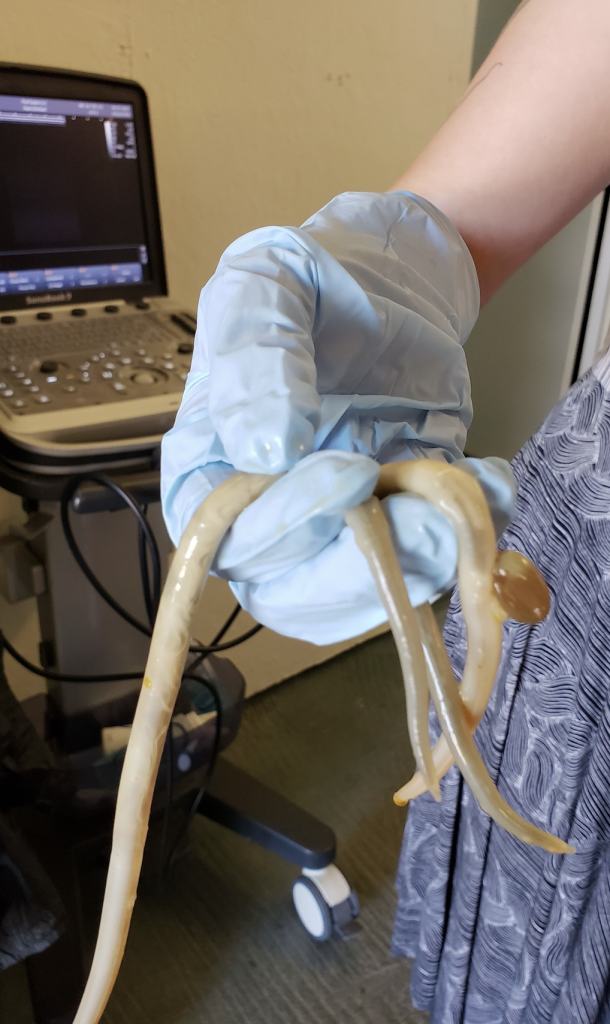

Adult Parascaris equuorum taken from the small intestine of a severely ill 4 year old mare who had been dewormed regularly. Seeing these parasites in adult horses is very unusual, but a sign of the resistant “super worms” that have become a huge problem for the equine industry.

Recently I had to euthanize a world-class 4-year-old Quarter Horse mare, a real tragedy. She had badly damaged intestines, and after 2 colic operations, we decided to put her down. Her problems were partly brought on by a severe infestation of large roundworms (Ascarids). This type of parasite is common in young horses but VERY rare in adults. My first thought when I saw all the large adult parasites at surgery was “Why isn’t this mare being de-wormed?” When I asked the trainer about her parasite control program though, she said she had been wormed every 5 weeks!

While this mare probably had a very rare “immune tolerance” to these parasites, what was most alarming was that the parasites were able to survive in the face of repeated dousing in de-worming chemicals. These worms were resistant to the de-wormers being used!

Adult Parascaris equuorum taken from the small intestine of a severely ill 4 year old mare. Seeing these parasites in horse over 2 years old is rare.

A Very Serious Problem

Resistance to our common de-wormers is a rapidly-growing problem that you should be aware of. Excessive and indiscriminate worming- people simply grabbing random products off the shelf and giving them to horses without having any idea of why they are doing it, or what they should really be doing- has led to the problem. Outdated parasite control theories and practices continue to perpetuate it.

In the last ten years, there has been increasing evidence for worm resistance to common de-worming chemicals. The scary thing is that if worms develop resistance to our available de-worming medication classes, we will no longer be able to protect our horses from worm-associated diseases.

Parasite resistance is a serious problem and will require that the whole horse industry change its way of doing things. It is critical that you, as a horse person, understand the nature of the problem, and help solve it. Simply de-worming your horses with a rotation of deworming pastes is no longer the best approach. Yes, you will need to de-worm, in order to keep your horses’ parasite numbers controlled. But the desire to eliminate worms has to be balanced with intelligent, targeted methods. To slow the onset of resistance, what will be required is actually LESS, but SMARTER deworming.

The History of Equine Internal Parasites

It is natural for healthy horses to have some parasites. Craig Reinemeyer DVM PhD, a renowned expert on equine parasitology, states the problem well: “Equine parasites have co-evolved with the horse over 60 million years of evolution. They are unique to the horse, and they can only survive if the horse survives. It doesn’t make sense for them to kill their horses, to burn down their only home. We need to manage parasites, not eradicate them. Our efforts at eradication are what have led us quickly to this problem of resistance.”

Common Parasites & Their Impact

There are more than 150 species of internal parasites that affect horses. Important groups for this discussion include:

Ascarids (Roundworms)– Large roundworms in young horses (Ascarids), can cause ill-thrift and at times (usually after de-worming), complete obstruction of the intestine.

Large Strongyles (Bloodworms)- The adults can cause life-threatening intestinal damage by blocking arteries supplying blood to the intestine. Large Strongyles have been made scarce since the advent of ivermectin.

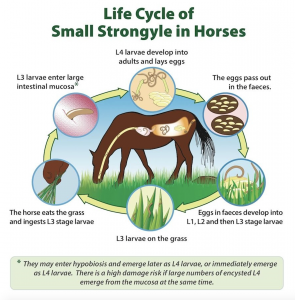

Small Strongyles- With the disappearance of large Strongyles, this group has actually become the most important, and the one that has shown the most resistance to common de-wormers.

Pinworms– their eggs adhere to the skin around the anus and cause itching of that area and the tail head. We are beginning to see resistance to common de-wormers.

Bots– The larvae live in the stomach and are not thought to cause much problem at all, although the egg-laying adult flies are highly irritating to horses.

Tapeworms- live in a particular region of the small intestine, and in large numbers can cause irritation and blockage of the that area. Tapeworms are more common in humid regions of the country, and require a field mite as an intermediate host.

Habronema worms transmitted by flies cause non-healing wounds called Summer Sores

There are many others too, but you get the idea.

It gets complicated. Any one, or all of these parasite types and others may be present in the horse simultaneously, and at different stages in their life cycles. Some worm species can lay hundreds of thousands of eggs per day, so parasite loads can grow quickly both on pasture and in horses. The different de-wormers have varying effectiveness against the types and stages of parasites. Intelligent control of parasites must take all these factors, and many others into account.

The Basic Parasite Life Cycle

While there are differences in the specifics among the life cycles of different parasite types, the general idea is similar. There are stages within the horse and stages in the environment. Parasites released into the environment in manure take time to develop into stages that can be swallowed by the horse, to survive and continue the cycle. Importantly, the climate must be “right” for this environmental development to take place.

Healthy horses have some internal parasites. It’s just the way it is, and it doesn’t hurt the horse. The parasites operate “behind the scenes” and horses with modest parasite population usually look perfectly healthy. You wouldn’t expect to see anything in the manure of a horse that has some parasites either. Most parasite eggs and the worms themselves are tiny or microscopic, and so are rarely visible in manure.

In contrast, horses with large loads of parasites can show a wide variety of signs of illness. The specific signs shown depend upon the specific parasite type in question, the horse’s general health and immunity, and the number of worms in the horse. For example, heavy small Strongyle infestations might cause horses to have gastrointestinal irritation and damage, reduced nutrient uptake and generally poor health. Horses affected by such a large parasite burden usually look like we would expect them to: pot-bellied, rough coated and/or thin. They might experience colic, or have diarrhea. But in reality, this sort of severe intestinal parasitism is relatively uncommon today in developed countries.

How the Resistance Problem Began

Far before horses interacted with humans, they lived with parasites. Parasites weren’t much of a problem for wild horses though. Herds of wild horses were on the move, leaving worm eggs in their manure far behind, to wither and die in the elements, thereby breaking the cycle of infection.

In contrast, modern domestic horses kept in smaller enclosures were not able to escape their manure, and so they picked up more infective parasites from their environment. The cycle intensified, and the severe effects of major parasite infestation became obvious. A half-century ago, severe parasite-related disease was common. Since then, however, effective de-worming compounds were developed that drastically reduced (and altered) parasite populations in horses. Make no mistake; de-worming chemicals have definitely helped the health of domestic horses. There is far less parasite-related disease than there was 50 years ago!

The cost of this extremely effective campaign, however, has been the development of resistance to these compounds, especially in small Strongyle parasites. Increasing resistance has resulted in the growing ineffectiveness of the drugs. We are beginning to see pockets of resistance to even our newest and most potent chemical de-wormer class (the one that contains ivermectin and moxidectin).

There’s another part to the story. Before the advent of modern OTC paste de-wormers, veterinarians were very involved in equine parasite control. 30 years ago, vets “tube-dewormed” horses on a schedule, meaning that they passed a stomach tube through the nostril and down into the stomach, and they dosed a large quantity of a chosen chemical directly into the stomach.

In the last 40 years though, paste formulations of the common chemical classes have become increasingly available and inexpensive. Equine caretakers have rotated de-wormers casually, not understanding the differences among the drugs or the parasites, and under the false assumption that “more frequent worming is better”. Veterinarians, including me, have been complicit in this approach. 20 years ago, I consistently recommended a “fast rotation” program to my clients without ever really considering the potential implications.

Unfortunately, resistance in the worm population means that we now need to completely re-think how we de-worm our horses. Misconception and lack of awareness by the whole industry has led to the development of a very big problem.

Without Change – The Future is Full of Worms!

In the past we assumed that if we rotated compounds, that parasites that were not killed by one class would be killed by the next. This idea worked pretty well when the 3 main chemical classes each killed the majority of parasites.

But it is a bad idea now, for these reasons:

-

Two out of the three main classes of chemical no longer kill parasites adequately. Parasites have become resistant to them. Their continued indiscriminate use will quickly result in COMPLETE resistance to these compounds.

-

Rotation using ineffective compounds ensures complete resistance to them while creating a false sense of security. The potency of the effective de-wormers “covers up” the inadequacy of the others in the rotation.

-

We are already seeing pockets of resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin (our last remaining effective class) and it is inevitable that this will increase. Use of these compounds without fecal testing will ensure a short effective life for them.

-

There are no new chemical compounds in the works right now. Research and development is costly and takes time. Our emphasis should be on extending the effectiveness of the drugs we have.

How Worms Become Resistant

Parasites develop “resistance” to the chemicals used to kill them, meaning that there will be worms in the population of a particular type of parasite that are not killed by a particular chemical.

Here’s how it works: Most parasites are killed by a single properly administered and effective de-wormer application. Out of thousands of worms of a particular type in a particular horse, there may be only a few surviving (resistant) parasites that have genetic differences that allow them to tolerate the chemical.

By chance, one of these few survivors could interbreed with another similarly resistant parasite, passing the resistance gene down, and producing resistant offspring in the next generation. These offspring survive, thrive and propagate in the presence of the chemical, resulting in the next generation being comprised of even more resistant parasites. These parasites would have a great advantage over the non-resistant parasites, only as long as the chemical is still in the environment.

The greater the percentage of the worm population that is exposed to the chemical, the greater the pressure for the parasite populations to develop resistance against it, and the faster the percentage of parasites becomes the new, resistant type. Of course, you would never see this process taking place. It all happens behind the scenes.

With enough time and exposure to de-worming compounds, it is inevitable that resistance will eventually take place. Careless and over-aggressive de-wormer use has and will accelerate the development of this resistance. Having said this, the goal should be to make the effective period as long as possible for each of our de-wormers. How do we achieve this? By MINIMIZING the exposure to these compounds through only “targeted” deworming.

Targeted De-Worming

The best way to prevent development of resistance to these compounds is not to use them at all! That would surely and completely eliminate any selective advantage for resistant parasites. Obviously though, this is not feasible, because our horses would again succumb to the effects of parasites.

However, leaving a SEGMENT of the parasite population with minimal exposure to these chemicals WILL slow the onset of resistance. In this way, susceptible (non-resistant) parasites are allowed to go on living and competing with the resistant parasites. This is known as preserving “refugia” within the worm population.

We can move toward this by only de-worming horses that have higher fecal egg counts. For horses with lower egg counts, we need to drastically reduce the number of de-worming treatments per year. Determining “who gets what” requires an understanding of which horses have higher worm burdens and shed more into the environment. This knowledge requires fecal testing by your veterinarian.

Start With Fecal Egg Counts

Fecal Egg Counts (Fecal Exams) are the cornerstone of targeted de-worming. Here is how they work: As we have said, adult worms live in the intestine and shed eggs that end up in the manure. Most worm egg types can be identified and counted using a microscope. Accurate testing requires knowledge of the technique and practice. There are limitations to FEC, as some species are difficult to diagnose this way. In addition, eggs may only be shed intermittently, meaning that even though adults are present, a given sample might not contain eggs and so the infestation would be missed. Even taking into accounts its’ limitations, FEC is still the best indicator we have of worm burden in horses.

By using fecal egg count results, horses are broken into 3 groups, those with high levels of shedding into the environment, those with moderate, and those with minimal. High Shedders are dewormed frequently- about 3 times per year. The moderate group is de-wormed less and the minimal group hardly at all.

The goals of this new approach are optimal horse health for all horses in the herd, reduced dependency on chemicals, and reduced contribution to the resistance problem. It relies on improved fecal diagnostics to monitor the effectiveness of the program. The key to this new approach to de-worming is working with your veterinarian. There is no perfect de-wormer and no standard program. Fecal testing guides the program.

Horses at different ages and stages have varying needs for parasite control. Twenty percent of horses in a group shed 80% of the total parasites. Young, growing horses have some special needs. They are especially susceptible to Ascarids (roundworms), and may benefit (regardless of fecal egg counts) from de-worming with an appropriate compound at 30-60 day intervals until they build some natural resistance.

Climactic conditions and season of year influence parasite levels in the horse and on pasture and are critical factors to address. The goal is not to kill ALL parasites, but to keep parasite loads to a level compatible with health, and to leave a reservoir (refugia) of parasites in as many horses as is practical. Based on all this, in our veterinary practice we recommend a fecal exam on every horse twice annually, in our area in May and October. Testing is the only way to determine the effectiveness of a parasite control program and to detect the development of resistant parasites.

Collecting a fecal sample is easy. Simply pick up 1 fresh fecal ball in a zip-lock bag, squeeze the air out of the bag, label it with your horse’s name, and drop it by your veterinarian’s office. You can store a fresh sample up to 12 hours if you keep it refrigerated. At our clinic, we do this testing in-house. We provide our clients with the results within 24 hours. It is important that the sample be taken at least 3 months after de-worming, and 4 months after de-worming with a Quest (moxidectin) compound. Otherwise the effect from the prior deworming confuses the results. If horses are on a continuous de-wormer like Strongid C, they can be tested at any time while still on the de-wormer.

What Your Veterinarian Does

-

Your vet assesses your overall program. This includes the risk to your horses, their management, your geographic region and environment. They help you tailor your program to these factors and to the results of Fecal Egg Counts.

-

They perform a fecal egg count on your manure samples and determine which horses are low (< 200 epg), moderate (200-500 epg) or heavy (>500 epg) shedders.

-

They identify the specific parasite types, allowing a determination to be made of the most effective de-worming compound fpr the situation. You will then de-worm the horses with that appropriate compound.

-

Once annually at least, they will perform a FECRT (Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test). To do this, you submit a second sample two weeks after de-worming. The veterinarian performs another fecal egg count on that sample. If the drugs are working the way they should, there should be no parasite eggs in the second sample.

-

They help you tailor a customized parasite control program. Horses are de-wormed with the appropriate compound based on their category.

-

The cost of fecal testing should be offset by a significant savings in the purchase of de-worming compounds.

Management is the cornerstone of parasite control. Chemical control is actually the less important part of a total parasite control plan. Since parasites are primarily transferred through manure, good manure management is key.

Click Here for some management recommendations for controlling parasites in your horses’ environment.

Conclusion

In the past, it was taken for granted that frequent rotational de-worming was the best way to reduce parasite resistance, but this has proven to be false. Parasite resistance is a real and growing threat. It is a problem that veterinarians and the horse industry need to work together to manage. Resistance is inevitable, but the goal now should be to slow its onset, and to extend the period of effectiveness of our currently effective compounds, while still maintaining the health of our horses.

By Douglas O. Thal DVM Dipl. ABVP, Board Certified in Equine Practice, Revised 2019

References:

Neilsen, Martin- AAEP Parasite Control Guidelines-

Kaplan, Ray DVM PhD. An Evidence Based Medical Approach to Equine Parasite Control , in “The Practitioner” October 2008;

Briggs, Karen, Reinemeyer, et al. Parasite Primer series in “The Horse” 2004; AAEP Pamphlet on Parasite Control, 1998;

Swiderski, Cyprianna DVM PhD, French, Dennis D. DVM DABVP Paradigms for Parasite Control in Adult Horses in AAEP Proceedings 2008.

Reinemeyer, Craig: Personal Communication 2014.