Systemic Antibiotics- What Horse People Should Know

Flash had a small wound on his lower leg that had taken forever to heal. His vet recommended an antibiotic for a week, but the owner didn’t think the wound was healing fast enough. She discussed this with her friend, not her vet. Her friend happened to have another antibiotic in her tack trunk. They added that one in too. 24 hours after starting the second antibiotic, Flash stopped eating, developed a fever, and then started pipe-stream diarrhea.

After 3 weeks in an equine referral hospital isolation barn and over $14,000.00 in vet bills, Flash was finally able to go home. He was crippled by laminitis, and he had lost one of his jugular veins. It would take him 3 months to return to being ridden again and he was never quite the same. Flash was one of the lucky ones though. Most horses that develop severe antibiotic-induced colitis do not survive.

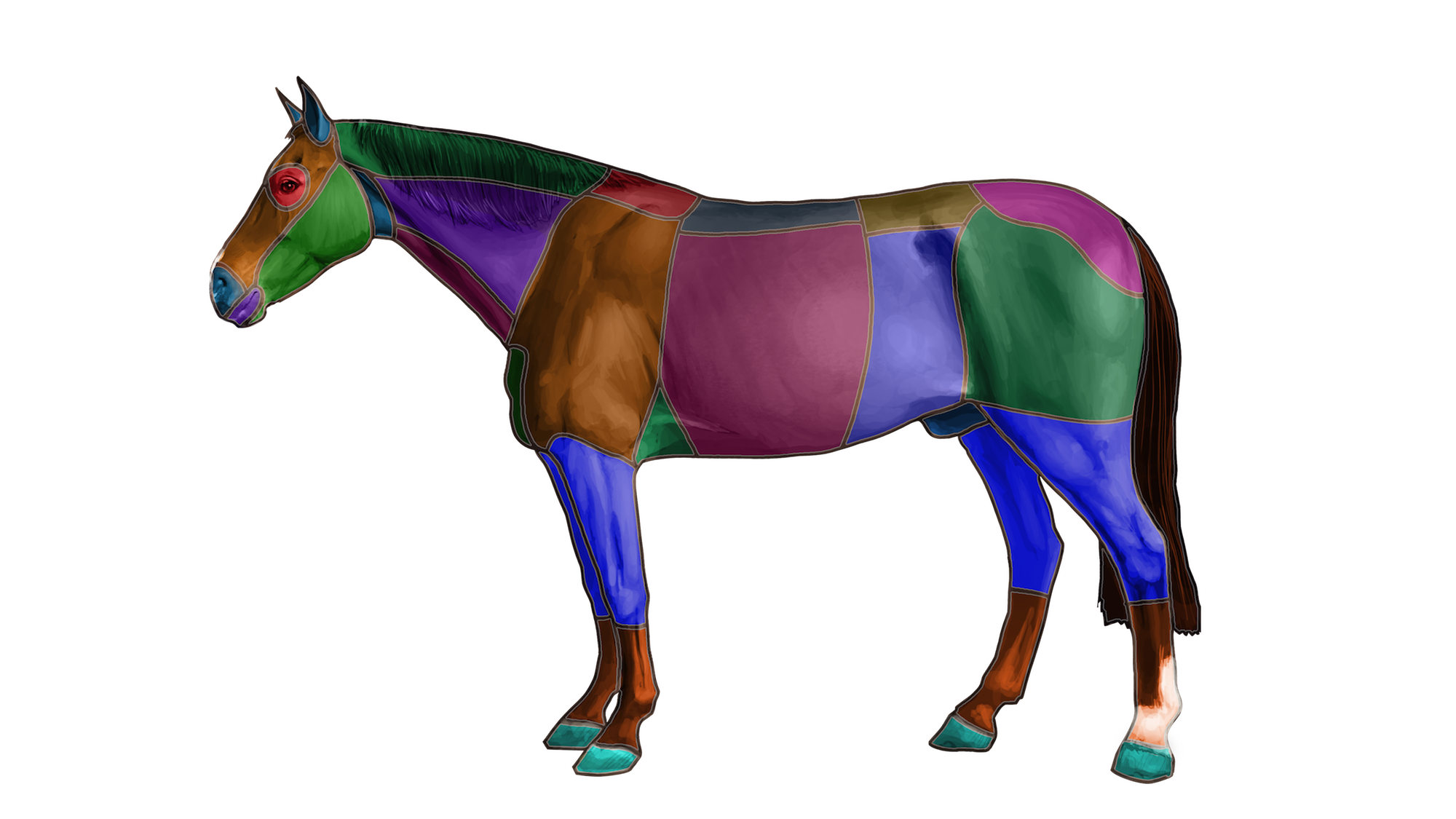

An antibiotic (antibacterial or antimicrobial) is a drug (chemical used in medicine) specifically used to kill bacteria or stop bacterial growth in the body. The word SYSTEMIC here refers to the whole body being treated, in contrast to LOCAL treatment, which might include, for example, topical antibiotic application (skin), ophthalmic (eye), otic (ear) intra-articular (joint), or regional limb perfusion.

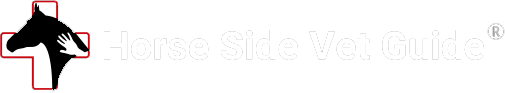

Systemic antibiotics are routinely misused in the equine industry. Misuse and overuse of antibiotics speeds the development of antibiotic resistance. When bacteria develop resistance to an antibiotic, the antibiotic will no longer work. With a very finite source of available antibiotics for both vet and human medicine, it is critical that we use antibiotics wisely in the equine health industry. Part of that responsibility lies with you: equine owners, trainers, and caretakers.

What would life be like without antibiotics? The truth is that people (and horses) would routinely die from what we now consider simple infections. Get a cold that turns to bacterial pneumonia? You die. Get an Infected cat bite? You’d be likely to lose your arm.

There is so much we take for granted when it comes to antibiotics.

A systemic antibiotic must reach THERAPEUTIC levels in the target tissue or organ, meaning that a concentration of antibiotic must develop that will kill or stop growth of the offending organism within that tissue or location. For an E.coli joint infection for instance, we need an antibiotic which, when administered by a given route, will develop a high enough concentration of antibiotic to kill that particular E.coli WITHIN the diseased joint fluid and tissues.

The TARGET ORGAN depends on the nature of the infection. Examples-The target organ for pneumonia (lung tissue), for peritonitis (abdominal fluid), for an infected joint (synovial or joint fluid), for bacterial encephalitis (brain). Each chemical class of antibiotic has properties that determine whether it can penetrate these tissues and achieve bacterial killing concentrations within them.

In order to work systemically, several steps must take place. First, the antibiotic must make its way into the bloodstream, where it must reach a sufficient level, which then allows it to spread to other tissues.

An oral antibiotic must first be ABSORBED into the bloodstream from the GI tract. An IM antibiotic is absorbed at a particular rate into the blood from the muscle tissue. An IV antibiotic goes directly into the bloodstream, so avoids this first step.

Once the drug reaches an adequate level in blood, it is then distributed from the blood to particular tissues within the body, at different levels, again dependent on the chemical structure of the antibiotic and its biochemical interaction with different tissue types.

SYSTEMIC antibiotics are chemicals administered by ORAL or INJECTABLE (intramuscular, intravenous, or rarely, subcutaneous) ROUTES, to specifically combat bacterial infections.

After giving a specific antibiotic by one of these routes, the drug is absorbed into the blood over a specific period of time, reaches a specific level in the blood over a specific time, ends up in specific body tissue types at specific levels, and at specific times, and then stays in those tissues for a specific length of time.

An antibiotic’s SPECTRUM refers to the range of bacteria that it kills. Antibiotics are called “BROAD SPECTRUM” when they kill a wide variety of bacterial types. “NARROW SPECTRUM” antibiotics, in contrast might only kill only very specific bacterial types.

Medical professionals choose specific drugs to target specific organs and bacteria. This is why it is so important to only give an antibiotic when directed to do so by your veterinarian.

Systemic antibiotics in horses are members of multiple distinct chemical classes, which kill or suppress bacteria in different ways, called MECHANISMS OF ACTION.

Examples:

~Penicillin and related chemicals (called ionophores) have a mechanism of action involving damage to the gram positive (Strep, Staph are examples) bacterial cell wall, causing the bacterial cell to burst.

~Gentamicin, an aminoglycoside, interferes with the ability of the bacteria to produce proteins essential for life.

~Sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim or sulfadiazine/ trimethoprim are given together, and each stops a biochemical step necessary for making the components of bacterial DNA, so preventing bacterial reproduction.

~Enrofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone, interferes directly with bacterial DNA synthesis.

~Chloramphenicol, the tetracyclines and erythromycin stop bacterial protein synthesis at unique biochemical steps.

Each antibiotic has a profile of characteristics that make it more or less useful for particular bacteria in a particular veterinary case.

Commonly used systemic antibiotics in equine veterinary practice include sulfadiazine/ trimethoprim (Equisul), sulfamethoxazole/ trimethoprim, procaine penicillin, gentamicin, enrofloxacin and ceftiofur. Less commonly used antibiotics are metronidazole, amikacin and chloramphenicol, among many others.

There are only a few antibiotics approved by the FDA specifically for use in horses for a particular purpose. An example of this is the brand name Equisul ®, which is sulfadiazine and trimethoprim. A drug like Equisul ® has gone through an extensive and expensive process to ensure safety and efficacy. Since there are not many of these, the majority of drugs use in equine practice are used in an EXTRA-LABEL fashion.

There are many other, less common and very narrow-spectrum antibiotics that might be used in very specific circumstances, say for resistant bacteria, but this would be based on culture and sensitivity results.

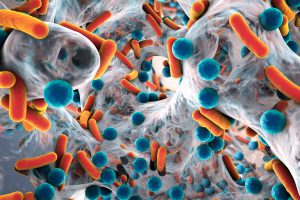

The use of antibiotics is controversial in both human and veterinary medicine. There is an important reason for this. When we use an antibiotic, we select for bacteria that can survive that antibiotic. If those survive, the resistant organisms become more and more common over time. For this reason, among others, we must use antibiotics intelligently.

YOUR VET’S ROLE WHEN PRESCRIBING OR USING ANTIBIOTICS IN HORSES

Vets choose to treat with systemic antibiotics if we think that the disease affecting the horse is being caused or worsened by bacterial infection, and we think that we have an antibiotic that when given systemically, may help combat this.

We may also choose to treat with systemic antibiotics to PREVENT bacterial infection. Examples are antibiotics given before and directly after surgery, or right after wounding, before there are obvious signs of infection.

Antibiotics may be given to prevent “secondary” infection. For example, viruses cause damage to the respiratory defenses, leaving the respiratory tract open to bacterial infection. We might choose to use antibiotics even though we know that the primary disease process is viral.

Equine vets must know the most common bacterial infections of various organ systems, and we regularly make educated guesses as to the bacteria causing them. When we talk about an antibiotic’s SPECTRUM, we refer to the range of bacteria that is killed or controlled by that antibiotic. If we are just trying to suppress bacteria generally, we may choose to use drugs with “complementary spectra”, meaning a combination of antibiotics that kills a wide variety of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. An example of this sort of combination is sulfadiazine with trimethoprim as a single medicine https://aurorapharmaceutical.com/equisul-sdt/ , or penicillin and gentamicin given separately.

In a perfect world, our choice of an antibiotic would be determined by laboratory culture and sensitivity of the organism, but in practice we rarely do this. Culture takes several days in the lab and adds significant cost to the case.

Much more often, we make an educated guess about the bacteria involved in a disease process, and then base our antibiotic choice on that. A vet’s preference should be to use one of the few antibiotics labeled for equine use, but in practice this doesn’t always happen.

Advantages of antibiotics-

~In many cases, an antibiotic may be the ONLY direct method for stopping a bacterial infection within an organ or tissue.

~In many cases, antibiotics can be given orally, allowing ongoing convenient treatment at home.

~In most cases, our commonly used antibiotics have few or no noticeable side-effects.

Limitations of antibiotics –

~Importantly, antibiotics are not a good choice to treat abscesses or closed infections (accumulations of infected fluid within a body cavity). These always require drainage and flushing.

~Antibiotics will not solve a chronic infection if there is dead or foreign material in a wound or body cavity. This must be removed or DEBRIDED first.

~Antibiotics do not treat viruses or, in most cases, anything other than bacteria.

~A particular antibiotic may not reach sufficiently high levels to kill bacterial infections within the infected tissue.

~Many antibiotics do not reach effective levels in the brain. The brain is protected by what is called the “blood-brain barrier”. Some antibiotics do cross this barrier.

~Oral antibiotics may not be well absorbed from intestine into bloodstream in the first place.

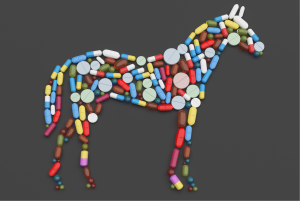

~An antibiotic may not distribute from the bloodstream into the infected tissue, and therefore not reach therapeutic levels where the infection is. This partly depends on the blood supply to a particular tissue. Antibiotics do not work well in areas with poor blood supply- an example of an area with generally poor blood supply is the hoof. A classic example of a disease process that is poorly suited to antibiotic use is a sole abscess. This is a closed infection, surrounded by hoof tissues that have very limited blood supply.

~Particular bacterial types may be resistant to particular antibiotics for a variety of reasons. The antibiotic chemical may either simply not work against a particular type of bacteria, or it may be that a particular bacterial strain has evolved genetically (BECOME RESISTANT) and can sidestep the antibiotic’s mechanism of action.

~There may be no FDA-approved, commercially available antibiotic suitable for a specific type of infection. This means that a drug must be used EXTRA-LABEL (outside of its legal proven and safe usefulness). In this case, vets may choose to use COMPOUNDED ANTIBIOTICS, made by COMPOUNDING PHARMACIES.

~Extra-label use of antibiotics should be avoided when there is an approved drug that would do the job.

~ANTIBIOTIC-INDUCED COLITIS– Horses have a massive large colon that houses massive numbers of vital bacteria (called the microflora), The bacterial population is critical for fermentation and digestion of roughage. The microflora is vulnerable to upset by the use of antibiotics, and so there is one great and potentially fatal side effect possible any time we use antibiotics in horses: ANY antibiotic can cause disruption of the microflora, and this can result in life-threatening diarrhea/colitis. There are certain antibiotic and antibiotic combinations that more commonly cause colitis, but it can happen with any systemic antibiotic.

~Soft or semi-formed manure (cow pie). This is related to disturbance of the microflora, but as long as it is mild, then we might choose to keep treating. That said, it is important to make your vet aware of this.

~Allergy: any drug, including any antibiotic, can cause an allergic response. This can range from a few hives to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

**Beside these general side effects, SPECIFIC antibiotics have SPECIFIC side effects, some of which are very severe. Examples: Enrofloxacin should not be used in young horses because it can cause cartilage damage in developing joints. Gentamicin and similar drugs may cause damage to the kidney or the inner ear (causing deafness). The carrier in Penicillin G procaine can cause a severe neurologic reaction (called procaine reaction) soon after injection. Sulfa antibiotics, when used long-term, can cause anemia.

~Antibiotics must be used cautiously in particular horses that are susceptible to colitis or other side-effect, for any reason. Maybe they have a history of colitis, for instance.

~We know that the patient is allergic to the drug,

~Vets carefully choose antibiotics, because the more antibiotic that is put into the environment, the more chance for bacteria to develop resistance to that antibiotic. If resistance develops in a bacterial population over time, the antibiotic loses its effectiveness. This can have profound consequences in veterinary and human medicine. So if we don’t need to use an antibiotic, we would rather not use one!

~Vets should choose an FDA- approved antibiotic when this makes sense for treatment

~There is poor evidence that bacteria are the cause of disease.

~Evidence from culture/sensitivity suggests that this antibiotic will NOT kill the offending organism.

~Closed infections usually require treatment at least in addition to antibiotics. Examples: an abscess must be drained, a septic joint must be flushed or opened, a peritonitis may need to be lavaged (opened and flushed). Within an abscess, antibiotics often do not reach high enough levels to kill bacteria.

~The horse is on other drugs that might cause an adverse reaction when given with the antibiotic.

~Why does my horse need antibiotics in the first place?

~What antibiotic side-effects might I look for?

~Do you know that bacterial infection (versus viral infection, trauma, cancer) are the cause of my horse’s disease?

~Is this antibiotic safe? What is the likelihood of this antibiotic causing diarrhea/colitis in my horse? Are there safer antibiotic alternatives? Should I expect soft manure?

~Will I continue this antibiotic at home?

~What should I look for to suggest the antibiotic is working?

~Since you have said my horse likely has viral disease, why are you using an antibiotic to treat him?

~Do you have proof (culture and sensitivity) that this antibiotic is going to kill the bacteria causing disease?

~Is the antibiotic you have chosen FDA approved for use in horses, for this use? Is this extra-label use of the drug?

Judging success- how do we know when an antibiotic is working?

When a vet assesses the effectiveness of an antibiotic, we usually look for improvement in the specific parameters of the organ system we are treating. In the case of pneumonia, for example, we might hope for improved lung sounds, reduced respiratory rate and effort, reduced heart rate, reduced fever, improved chest ultrasound findings, improved blood gases and other blood test results, among many others. All these findings would suggest that the bacterial infection is being weakened by the antibiotic. Of course, there could be other explanations for this as well.

In the case of an infected limb (cellulitis or sporadic lymphangitis), we might hope to see reduced lameness and swelling and improvements in blood tests.

Along with physical exam, we often use particular blood tests to assess effectiveness of antibiotic treatment – particularly fibrinogen and SAA, as well as changes in the white blood cell count.

YOUR ROLE AS AN EQUINE CARETAKER

Don’t take antibiotic use in the horse lightly! Responsible antibiotic use means:

~You should understand the potential benefits but also the limitations and dangers of systemic antibiotic use in horses.

~You should always use antibiotics under the direction of a licensed vet, experienced in equine medicine.

~You should recognize how fragile the equine intestinal microbiome is compared to that of other species. Know that disturbing it through the use of antibiotics can in rare cases mean the death of the horse.

~You should understand and respect the danger of development of bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

~You should know the few antibiotics approved for use in the horse, and that other use of antibiotics is extra-label. If there is an FDA-approved antibiotic for a given use, your vet should ideally select that over an extra-label antibiotic. It is ok to ask them about this- have the discussion.

~You should have the skills to properly administer the medication. Here are a few skills that I list in Horse Side Vet Guide, which you might need to be able to treat your horse with antibiotics:

Assessing treatment effectiveness: https://horsesidevetguide.com/drv/Skill/194/assess-effectiveness-of-treatment-objectively/ As the horse’s owner, you have a vital role in providing feedback as to how a treatment is working. In this way, adjustments can be made in treatment plan.

How to give oral Medication: https://horsesidevetguide.com/drv/Skill/28/give-oral-medication/

Assess your horse’s general health: https://horsesidevetguide.com/drv/Skill/146/perform-whole-horse-exam-whe/

What you might observe when a horse is on antibiotics depends on the type of infection and the specific signs your horse has been showing, as well as the nature of the antibiotic being used. In general, you should see improvement in your horse’s condition in hours to days; or at least your horse’s condition should not worsen. Again, your vet will provide the specific signs to watch for, but you may need to ask for those specifics.

Here are examples: A horse that is being treated with antibiotics for an infected wound: you should see the wound becoming smaller, with less drainage or swelling. If an antibiotic is being used as part of the treatment of an infected joint, you might expect to see continued improvement in lameness and reduced swelling of the joint. If a horse is being treated for peritonitis or pneumonia, your vet may ask you to continue to monitor attitude, appetite and rectal temperature as an indication of whether or not the antibiotic is working.

Through your own antibiotic awareness, and proper antibiotic use, you are protecting your horse’s health, and you are also preserving these vital drugs for human and animal use in the future.

Thanks to Aurora pharmaceuticals for sponsoring this article, and Horse Side Vet Guide. We greatly appreciate your support!