Breeding mares with artificial insemination (AI). What you need to know.

Breeding a favorite mare, watching her go through her pregnancy, and then have a beautiful foal by her side. It’s idyllic when it all works out well, but you need to go into it with your eyes open. There is a lot you need to know about the realities of the process, and you need to be aware of the cost and risk.

You also need to consider whether bringing another horse into the world is the right thing. This is a whole other matter that we can discuss in another article.

Why artificial insemination?

Artificial insemination (AI) offers huge advantages for breeders. It allows selection from a wide variety of genetics, from all over the world, and allows breeding of your mare without transporting her. Beyond the convenience factor, you are also protecting the mare from the costs and hazards of travel and from potential exposure to infectious disease at the breeding farm. Travel and changing facilities are stressful too, and a stressed-out mare is less likely to be a fertile one.

Important Background

Mares are seasonal breeders (called seasonally polyestrus). During the winter months of each hemisphere, most mares are reproductively dormant. In the northern hemisphere, mares begin having regular heat cycles again in March-April and this continues until November.

There is a period at the beginning of the breeding season called spring transition, in which many mares have irregular and unpredictable heat cycles. This is a risky time to breed with artificial insemination. Successful AI depends on timing insemination with ovulation. During spring transition, ovulation can be hard to predict.

Photoperiod (day length) is what drives a mare’s reproductive rhythm. One way to get a mare to cycle early in the year is to put her under artificial light for a given number of hours, starting the prior fall. This tricks the mare’s endocrine system into thinking that it is spring in January. Otherwise we limited to the usual breeding season.

Factors you need to consider before you commit to breeding your mare.

Start by knowing whether your breed association rules regarding artificial insemination. Most do allow AI, but notably, the Thoroughbred association (the Jockey Club) only allows natural breeding. (Section V, Rule 1D) The Principal Rules and Requirements of The American Stud Book is available on the Internet through The Jockey Club web site at http://home.jockeyclub.com/rules/index.html.

The cost: Breeding a mare with artificial insemination adds up from a cost standpoint. First, there is the stud fee, which is the cost for the semen itself and the right to register the resulting foal. Stud fees range from hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars or more, depending on the stallion.

Collection and shipping fees per cycle (often called chute fees) add up to hundreds more per heat cycle.

The semen will need to be shipped, which incurs express postal or airline fees.

Once the semen arrives, there will be mare management, ultrasound and insemination fees, usually performed by an equine veterinarian at their facility. The mare’s cycle must be monitored carefully, to properly time the insemination with her ovulation at the end of her heat cycle. Mare veterinary services can be $1000.00 or more per cycle.

Not every mare breeds on the first cycle. Success rates per cycle depend on many factors. Semen quality, either cooled or frozen, is a huge factor. Mare fertility- age, general health, reproductive health and properly timed breeding complete the picture. Young mares are generally easier to breed. Cooled pregnancy rates average 70% +/- while rates with frozen semen might average 40%.

The timing of the foal’s birth the following year:

This might depend on your intended use. For racehorses there is often a strong incentive to have an early foal. The older foal will be larger and more able to race as a 2-year old. On the other hand, for recreational horses, it might be fine or even desirable to have a later foal. Your local climate plays an important role here. If you have an early spring foal, what will the weather be like in your area? You don’t want a February or March foal if you live in a very cold climate.

Gestation in mares is about 330 days (about 11 months) for average horses, averaging longer for larger horses. There is a huge variation though, with the range being 320-400 days. Individual mares do tend to be fairly consistent in their gestation length year to year. Anything under about 315 days is considered premature. A premature foal can be a disaster.

So, if you breed in May, you would typically get an April foal.

Where will your mare foal? Might it be in your back yard, at pasture, or in a heated stall at a foaling facility?

You have found the stallion you want to breed your mare to, and now you need to consider the breeding contract:

You need to read the fine print of your breeding contract. Just what are you buying? There should be a “live foal guarantee”. What does that look like? Usually the guarantee is for a foal to be standing and nursing at 24 hours of age. Once the foal achieves this, you are on your own. If the mare aborts, or the foal is stillborn or never stands to nurse, typically the stallion owner will honor another breeding. Additional chute, shipping and breeding fees typically will apply.

Typical questions answered in the contract, or by the breeding manager.

- What are the shipping costs and chute fees per breeding?

- How many heat cycles will they willingly ship?

- What days is the stallion collected? How much notice is required to get a semen shipment?

The stallion end:

Getting cooled or frozen semen requires professional help at the stallion end. Breeding farms often “stand” popular stallions and collect semen from them on a regular semen collection schedule, often 3 times per week. We will need to know what those days are and how much notice they will need for shipment.

How does the stallion’s semen cool and ship? Some stallions have semen that tolerates cooling well and remains viable even at 48 hours post-collection. The viability of most semen drops off rapidly by 48 hours.

Once deposited into the mare’s uterus, semen can live for several more days.

Success rates are much higher if the mare is inseminated within 24 hours prior to ovulation, or up to 6 hours after.

Stallions learn to ejaculate into an artificial vagina (AV), which is a specialized large rubber tube with a reservoir end to catch the semen. The semen is collected, filtered, and assessed for concentration and motility using specialized equipment. A “breeding dose of semen” (how many ml of semen required) is different for each stallion depending on the concentration of his sperm. From the standpoint of maximal chance at conception, there is a minimum effective breeding dose of 500 million sperm deposited into the uterus of the mare.

Once collected, the semen is filtered, mixed with an extender, analyzed (a mix of skim milk, antibiotics and other nutrients) and based on the analysis, is split into these breeding doses. It is cooled in a special cooling/shipping container that maintains temperature at 37 F for at least 48 hours.

Semen is usually express-shipped using an overnight carrier. Rarely, a stallion’s semen has such a short life once cooled that it must be shipped “counter to counter” by air, such that the mare can be inseminated within hours of collection.

Properly prepared shipped semen arrives with paperwork that shows the semen concentration, motility, total volume and total dose.

The veterinarian breeding the mare examines the semen under the microscope to ensure that it is alive and well and roughly correlates to the claimed numbers on the sheet.

The container usually needs to be rapidly shipped back to the breeding farm (usually also at the mare owner’s cost) once the semen has been removed and used.

Mare factors

Your local equine veterinarian often will be the one breeding your mare. Ask them if they are experienced in breeding mares with either cooled or frozen semen. Are they set up to house your mare at their clinic, or will they be making repeated trips to your facility to assess your mare and time the shipping and breeding? Talk to them about cost, and how they will handle repeat breedings.

Breeding soundness exam prior to breeding?

In younger mares, a uterine biopsy is not always a necessary part of a breeding soundness exam. Mares that are not reproductive gradually become less fertile. A mare that has never been bred is known as a maiden. As a maiden mare reaches 9-11 years of age and older, her chances of conception become gradually less, and the risks of pregnancy and foaling gradually increase. This is not to say that old maiden mares cannot be successfully inseminated and carry to term, but the process of conception is often more complicated and expensive. When dealing with older mares, or when it is advisable to perform a uterine biopsy to assess the mare’s suitability and to determine the steps needed to ensure the best possible result for you and your mare.

Is the mare reproductively healthy? Ideally, you have your mare examined by the vet that will perform the AI, prior to breeding. If your vet has performed a biopsy, these results will be evaluated in conjunction with a full history and physical exam.

A young, healthy mare is usually the best candidate. Mares that are less likely to conceive and carry a foal to term are older mares or mares that have been difficult to breed in the past. It is important to note that even if a mare has had difficulty conceiving during her maiden year, it is possible that in subsequent years she will have no difficulty at all.

At a minimum, the vet palpates and ultrasounds the reproductive tract. It should be normal. Some breeding contracts will require that the mare have a negative uterine culture.

Is she cycling normally? Most mares are not cycling in winter and early spring. Ideally mares are allowed to enter the breeding season before attempting to breed them. Mares in spring transition may have irregular heat cycles that drive everyone crazy and don’t end up successful. In our practice in the USA, I usually suggest breeding mares starting in April and through June- the peak of the season and the peak of mare fertility.

If you want a very early foal, you must prepare the mare starting the prior fall, by exposing her to increased light. This tricks her system into thinking that it is the breeding season. It is the only way to do it.

Control of the estrus cycle- Successful AI requires coordination of multiple variables- it is all about timing, so we do use drugs to help control the heat cycle and ovulation so that we are better able to breed right around ovulation.

Frozen semen provides an advantage here as it is usually stored at the facility and can be used at any time. But the trade-off is that there is reduced conception per cycle. Also, insemination must be timed even closer to ovulation- ideally within 6 hours of ovulation instead of 24. We use a deep horn insemination technique to deposit the thawed semen right near the tip of the uterine horn, close to the oviduct (fallopian tube) of the ovary with the ovulating follicle.

We have probably given a prostaglandin the prior week to “short-cycle” the mare and take control of the cycle. Most mares will be in heat in a few days after that and ovulate about a week after the prostaglandin shot. That is when we usually have them arrive at our clinic. If we have a resident stallion, we may “tease” the mare to assess her degree of estrus and receptivity. This involves leading her near the stallion and observing both of their behaviors.

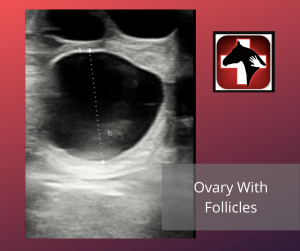

We begin daily ultrasounds of her reproductive tract, tracking the size of her developing ovarian follicles, especially the large dominant ovarian follicle (egg). The uterus and cervix also change as the mare goes into heat, showing the effects of estrogen from the large follicle. The ultrasonographic appearance of the uterus changes in response to estrogen, and the cervix softens.

As the follicle grows, we coordinate with the breeding farm to have the semen arrive just prior when we expect ovulation. We must avoid having the mare ovulate on holidays and weekends whenever we can, because of the need to ship the semen and have it arrive when we need it.

We often “take control of ovulation” by using drugs like HCG and deslorelin. This helps us predict when the mare will ovulate and time insemination closer to ovulation.

On ultrasound, near ovulation the dominant follicle looks like this:

Most mares ovulate follicles 35-45mm in size. They change shape and become soft as they near ovulation.

The mare is inseminated. A plastic AI pipette is passed gently through the mare’s cervix and the semen is injected into the uterus.

For frozen semen, the semen must first be thawed in a water bath at a very specific temperature and ideally delivered deep into the uterine horn with a specialized pipette.

Either way, we place a semen sample on a warm slide and examine the semen for motility. If the mare has not ovulated, then on

the following day we ultrasound for ovulation. Once ovulated, the mare can return home.

Motile semen moves up the uterus to the oviduct, where it meets the recently ovulated egg, and fertilization takes place.

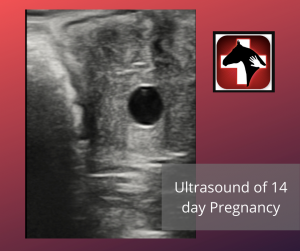

Her pregnancy check is usually 14 days after ovulation. A typical pregnancy looks like this.

Stumbling blocks- Things don’t always go as we would like, which can be very frustrating. Here are some examples of common issues

Some mares don’t ovulate when they should. The semen arrives, we inseminate the mare, and her huge follicle just sits there. A day passes, we recheck, it is still there! This can be extremely frustrating. It likely happens because of hormonal insufficiency or lack of sensitivity to hormones. Some of these mares are also insensitive to the ovulatory drugs we use.

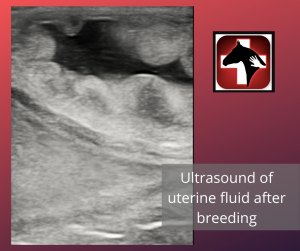

After insemination, some mares (especially older maidens) become inflamed, pooling uterine fluid or worse, become infected. Mares that have fluid in their reproductive tract 24 hours after breeding will likely not conceive.

Old maiden mares can be a real trick. Their cervix never softens, and so the natural emptying of the uterus doesn’t occur.

We treat retained uterine fluid and post-breeding endometritis by flushing the uterus after breeding, and we use drugs that contract the uterus down to expel this fluid. No, the semen that was just put in is not expelled.

Sufficient semen has collected high up the tract above the area that is flushed and awaits the newly ovulated egg. Flushing creates a clean, hospitable environment for the newly fertilized egg, the embryo. Post-breeding treatment does add to the cost of the hospital stay.

Conclusion:

Breeding your mare through artificial insemination can be a rewarding and exciting event. It requires a thoughtful matching of not only your mare, but of the prospective stallion. It also requires impeccable timing. Cooperation between the mare owner, the stallion owner, the veterinarian, and hopefully a good dose of hormonal luck between all parties involved. Check with your veterinarian to get a fuller picture of whether or not this process fits with your plans and your budget.