Common Veterinary Tests to Diagnose Conditions Causing Colic (CCC’s)

A percentage of horses that experience colic and are treated by a veterinarian in the field will continue to show signs of colic after the veterinary visit. When that happens – for the life of the horse – it becomes critical to make rapid decisions about how to proceed. As a horse persists in colic pain over time, it becomes more likely that a comparatively more severe condition is causing it.

Remember that the term “colic” simply means abdominal pain. There are many potential causes (diagnoses) that result in this pain, what I call Condition(s) Causing Colic or CCC’s. Whether a horse improves on its own, or how it responds to a particular treatment ultimately depends on the particular CCC that is affecting the horse.

Terms like “gas colic” “spasmodic colic” or “drop in the barometer colic” usually refer to horses that get better with walking and a little time, or improve after simple treatments like flunixin meglumine (Banamine®). In reality, these are imprecise terms because the CCC was never really identified. These terms are really just guesses as to what happened. Everyone involved is usually just grateful that the horse recovered.

This post describes the common diagnostic tests that are used at equine hospitals to evaluate the horses that do not respond to simple field colic treatments. The goal of these tests is to identify the underlying CCC'(s) and choose an appropriate treatment plan. Often a precise diagnosis is not possible. In this case, the goal is to differentiate between horses that require colic surgery and those that do not.

This list is not comprehensive or absolute. Depending on the facilities, available diagnostic equipment and particular case, additional or alternative diagnostics may be recommended by the veterinarian at the equine hospital.

If you are in the horse business long enough, you will ultimately be faced with a horse that shows persistent or severe colic signs. It is a stressful situation, and you will have to make quick decisions. I wrote this article for you.

You can also find much more detailed information on each of these tests in this website and/or our mobile app. Horse Side Vet Guide® is a constantly growing encyclopedia of equine health information we have created for horse owners and all equine caretakers. This website is free – and the mobile app is just $5 and is available on iTunes & Google Play. (I’ve included links to various diagnostic records in this blog post, should you want to read about each of them in greater detail.)

COSTS & FINANCIAL CONSTRAINTS

Colic diagnostic testing and treatment is costly, so it is important to discuss any cost constraints with your veterinarian up front.

Although less than 10% of all colic cases are surgical, you should be prepared to decide whether or not your horse is a candidate for surgery. See our related blog post: Colic Surgery: What Horse Owners Should Know for more information.

HISTORY

The examining veterinarian usually will ask you a series of questions about the horse. In many cases, they may have also acquired some of this information in discussion with the referring veterinarian. This kind of information can provide important clues regarding the CCC.

Questions a vet might ask include:

· The horse’s breed and age. (We expect specific CCC’s to be more common in older horses, or horses of particular type or breed.)

· Management and feeding of the horse, including any recent changes.

· What specific signs of colic the horse has been demonstrating? For how long?

· Have you (or the referring vet) given your horse any medication? If so, what, how much & when?

· What is your past approach to preventative healthcare for the horse?

· Any recent vaccinations? Deworming? Dentistry? Farriery? Other treatments?

· What is the horse’s past medical history?

· Has the horse experienced colic before? If so, how recently?

· What do you do with the horse (pleasure, performance, pet)?

· Do your other horses appear ok?

The veterinarian may ask many other or different questions, depending on the circumstances. Likewise, if you have additional information that you think may be helpful, be sure to tell the veterinarian. Sometimes seemingly irrelevant information can turn out to be a valuable and relevant clue to identifying the underlying CCC.

THE PHYSICAL EXAM

Assessment of a colic patient starts with a careful physical exam tailored to the situation. However, if the horse is in severe pain, the exam may be brief because the veterinarian is forced to provide pain relief and sedation to allow examination in the first place.

Once pain-relieving medications have been given, it can be harder to reach helpful conclusions from the exam results. The drugs will have “masked” the horse’s normal response to pain and changed their vital signs.

Of particular importance in horses experiencing abdominal pain include:

· Pain level and duration, and our ability (or inability) to control the pain with various drugs.

· Cardiovascular status: including heart rate, gum color, pulse strength and capillary refill time.

· Rectal temperature can indicate the presence of absence of infection or intestinal damage.

· Intestinal motility (the presence or absence of normal intestinal movement.)

· The presence (or absence) of bloating (abdominal distention).

· The horse’s body condition, attitude, coat and weight all provide clues to the CCC.

RESPONSE TO PAIN RELIEVERS

By the time a horse is brought to an equine hospital for further workup, they have likely already been given flunixin meglumine (Banamine®) and other pain relieving medications. These drugs often mask the signs of pain, without solving the underlying condition. Once the pain medication wears off, the horse often returns to showing signs of pain. See our other blog post: Bute & Banamine: What Horse Owners Should Know for more information.

The examining veterinarian must consider the effects of these previously administered drugs when they examine your horse, to see past their expected effects.

Particular CCC’s may produce pain that is more or less responsive to pain medications. Consequently, how a particular horse responds to pain medication is one more clue to the CCC.

Note: Along with pain relief, most sedative drugs cause decrease of the normal food-propelling movement of the intestine (intestinal motility). This is generally undesirable, so we try to minimize the use of these drugs when possible.

PASSAGE OF NASOGASTRIC TUBE

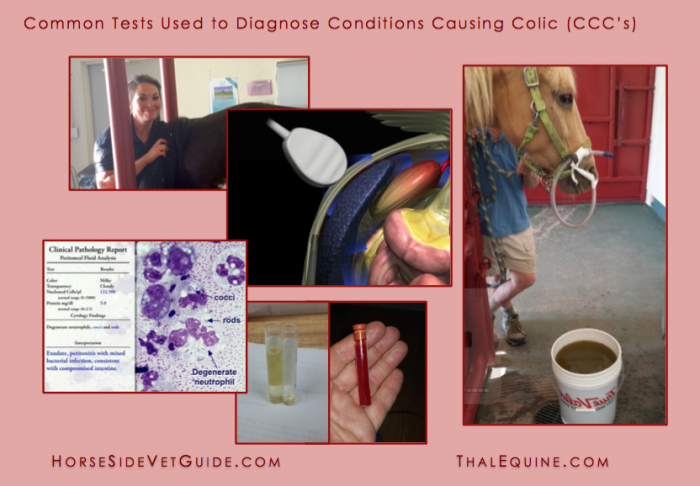

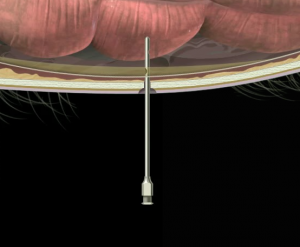

Stomach tube in the esophagus, on its way to the stomach. Image courtesy of The Glass Horse.

One of the first steps a vet takes in diagnosing a colicy horse is to pass a nasogastric or stomach tube into the stomach. Horses have a small stomach, and it is important to determine whether it is under pressure from backed up gas or fluid. What comes out of the stomach into the tube (gas, fluid or nothing) is a clue to the nature and location of the intestinal problem.

We removed over 5 gallons of reflux from this horse’s stomach using a nasogastric tube.

In this common procedure, a long, flexible rubber tube is inserted through one of the nostrils, goes through the nasal passages, pharynx, and follows the esophagus into the stomach. In the average adult horse the distance from the nostril to the stomach is over 6 feet.

In passing a stomach tube, the veterinarian must be sure that the tube passes through the correct nasal passage, encouraging the horse to swallow the tube to begin passage into the esophagus, and then guides the tube through the tight valve into the stomach. When the tube enters the stomach there is usually a rush of gas and a typical fresh grass or hay smell.

Of course the tube must not end up in the lungs. If fluid is pumped into the lungs, it will likely be fatal to the horse. So you should never try this procedure yourself!

Passing a stomach tube is a common skill practiced in equine vet medicine, but smooth, easy stomach tubing is an art that requires good horsemanship and technique. Some horses tolerate the procedure well, while others resent it and might require a twitch. How well the horse tolerates it generally relates to a combination of a horse’s ground training and the veterinarian’s skill.

Horses that are accustomed to getting their way may resist this procedure strongly. Very rarely, a horse has insufficient training in hand to tolerate this and they require sedation in order to safely pass a tube. In most cases, however, a skilled vet can make the passage of a stomach tube look easy, usually without a twitch or sedation.

Rarely, a horse experiences a bloody nose during or following this procedure. This results from abrasion to delicate membranes in the nasal passages by the tube. It usually results from the horse struggling when the tube is being passed, but it can also result from the tube going in the wrong passage and hitting a particularly vascular “dead end nasal passage”.

Even a bad nose bleed is usually relatively minor hemorrhage for a horse, so although it looks bad, it is usually not a problem for the horse.

Many horse people don’t understand that passage of a nasogastric tube can be used diagnostically, AND as part of treatment:

As a Diagnostic Test: Nasogastric intubation helps determine the presence or absence of fluid or gas accumulation in the stomach. In a normal horse, there should be little fluid reflux returning in the tube and only a small amount of gas.

If there is significant fluid accumulation in the stomach, it often means that there is a blockage (either physical or functional) of the upper part of the intestinal tract (the small intestine), which is causing backup of fluid into the stomach. This abnormal accumulation of fluid is called “reflux.” Knowing whether or not there is reflux is important diagnostic information.

As a Treatment: The major treatment objectives of nasogastric intubation are first to relieve overfilling of the stomach in cases where this is causing pain or contributing to the disease process. In cases in which there is not already backup of fluid into the stomach, the vet might choose to administer fluids and other medications into the stomach.

The most important effect of this is probably to stimulate a reflex that the downstream intestine and colon to move- a system called the Gastro-Colic Reflex. The fluid also MIGHT help somewhat with hydration. The laxative (lubrication) effect is actually less important than most people think, for a variety of reasons. Not every colicy horse will benefit from mineral oil and in some cases it could be harmful!

RECTAL EXAM

Happy young & talented vet performing a rectal exam.

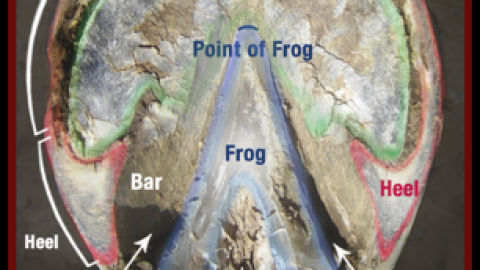

In a rectal exam, a veterinarian places a gloved, lubricated arm into the horse’s rectum in order to feel the anatomy of the back half or so of the abdomen. The rectum is thin- walled, and with careful examination, an experienced equine veterinarian can feel and evaluate many of the abdominal organs through the wall.

Structures such as the left kidney (the only one of the kidneys we can reach), the large colon and other parts of the intestine, the inguinal rings, the bladder and parts of the reproductive system can be evaluated.

A specific problem with the intestine or other organ is SOMETIMES diagnosed with this exam. More often though, a vet is able to determine what GENERALLY is going on by feeling gas or fluid distension patterns or a specific segment of intestine in the wrong position in the abdomen. Sometimes the rectal exam findings are completely normal, and this in itself is very helpful information.

Most horses tolerate rectal exam pretty well, but in some cases a vet may need to sedate or twitch the horse for this procedure for better relaxation of the horse and the rectum.

A very rare, but potentially severe complication of rectal examination is tearing of the delicate rectal wall. While this is a very uncommon complication, a severe rectal tear can be fatal. So there is a small risk associated with rectal exam.

MANURE RELATED DIAGNOSTICS

Tests for blood or protein in the manure may suggest bleeding or protein loss into the gastrointestinal tract.

Sand sediment test using rectal sleeve.

Sand accumulation is a common CCC in certain geographic areas. A sand sediment test is often performed to indicate the presence of sand in the manure, a potentially important finding. But a negative sand sediment test does not absolutely rule out the presence of sand in the GI tract. See our other blog post about Sand Colic in Horses.

Although often performed in horses showing colic signs, Fecal Egg Counts may or may not be useful in determining whether parasitism is the CCC. Fecal Egg Counts are an indicator of shedding of parasite eggs but not necessarily parasitic disease.

ABDOMINAL ULTRASOUND

Abdominal ultrasound is a very helpful diagnostic tool for horses that have not responded to routine colic treatments. .Abdominal ultrasound may be achieved either trans-rectally (through the rectum) or through the abdominal wall (trans-abdominally). Trans-abdominal ultrasound is much more commonly used in colic patients.

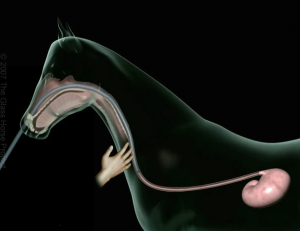

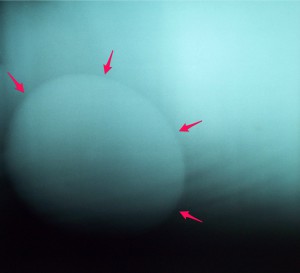

Ultrasound probe placed on the left abdominal wall. Image courtesy of The Glass Horse

An ultrasound probe emits sound waves that pass through tissue at various speeds depending on specific tissue characteristics. The sound waves bounce back to the transducer and a digital picture is produced by computer analysis of the returning sound waves.

Ultrasound is a wonderful tool for gathering more information about the equine abdomen. It can give additional valuable information regarding the position and state of various parts of the intestine. It is also used for evaluation of the tissue characteristics of liver, spleen and other abdominal organs, and for assessing the amount and characteristics of the abdominal fluid (the fluid that bathes the intestine and abdominal organs).

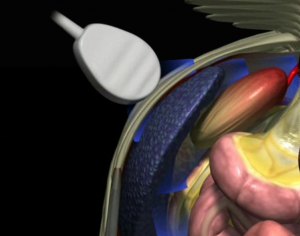

Ultrasound image of the left kidney & spleen in normal position. Image courtesy of The Glass Horse.

One limitation of ultrasound is its inability to penetrate gas-filled structures or solid feed. Another limitation is the relatively shallow penetration of the sound waves- only 6-12” at the most. How deep we can image depends upon the ultrasound machine and probe.

Like many other diagnostics, the quality of the information is only as good as the skill of the veterinarian performing the procedure.

BLOOD WORK & OTHER LAB TESTS

An in house hospital laboratory rapidly provides important information for making decisions in complicated colic cases. Additional special tests may still need to be sent away to a commercial laboratory. The results may take several days or longer.

COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT (CBC)

A complete blood count includes a count of red blood cells and several populations of white blood cells. A complete blood count gives valuable information about the general health of the horse, its hydration status and certain characteristics of the disease process. A white blood cell count is especially helpful in supporting a diagnosis of bacterial infection, or can suggest intestinal damage or endotoxemia.

BLOOD CHEMISTRY

The blood chemistry is a battery of individual blood tests for levels of about 20 enzymes and molecules within the liquid portion of the blood (the serum). Serum enzyme level increases can indicate damage to specific organs.

An example of a serum enzyme is LDH (lactate dehydrogenase). This enzyme is found only in liver and muscle cells. Large elevations in this enzyme can mean that either liver or muscle cells have been damaged, and that their enzymes have been released into the blood.

Veterinarians often need to review all the test results to interpret the significance of individual test results. Examples of other levels measured in a chemistry are glucose (blood sugar), creatinine (an indicator of kidney function), and many others. Total protein and albumin can be indicators of hydration status. A decrease in these can indicate loss of protein through a damaged intestinal wall.

Electrolyte values say something about the general health and hydration status of the horse and can also provide clues about needed resuscitation and treatment.

BLOOD & ABDOMINAL FLUID LACTATE LEVELS

Lactate measurement can be a helpful diagnostic test for horses showing signs of colic.

Lactate (lactic acid) is produced by tissues that are deprived of oxygen for any reason. In horses showing colic signs, high lactate levels can be associated with severe dehydration and shock. Blood lactate also rises when segments of intestine are damaged or have poor blood supply.

Lactate analysis can be performed on blood and/or abdominal fluid. Each provides useful information. The difference between blood and abdominal fluid lactate levels can also be helpful.

Changing levels of plasma and peritoneal lactate can indicate whether a case is improving or worsening with treatment.

ABDOMINOCENTESIS a/k/a BELLY TAP

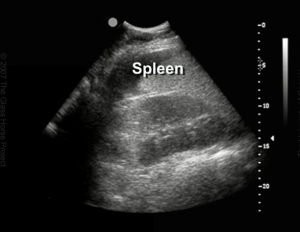

Insertion of sterile tube to obtain sample of abdominal fluids. Image courtesy of The Glass Horse.

An important and common test used in cases of abdominal illness in horses is abdominocentesis, commonly known as “belly tap”. This involves the collection of a sample of the free fluid from the abdominal cavity. This fluid bathes the outside of the intestine and abdominal organs. A normal 1000lb horse only has about 50 ml (2 ounces) of this fluid bathing the surfaces of the organs.

Changes in this fluid, both the quantity and appearance of the fluid and the laboratory results, give helpful information regarding the health of the abdominal organs, especially the intestine.

Certain changes in the fluid suggest damage to intestine and so can help determine the need for colic surgery or intensive care and can provide information about prognosis.

The Belly Tap procedure involves clipping the hair and carefully disinfecting a specific site on the lower belly. A needle is introduced carefully into the abdomen, using special care not to puncture intestine or other organs. The needle is maneuvered until fluid is encountered, and a small sample of this is collected into several types of blood tubes, for different tests.

There are different techniques used to harvest this fluid. In our practice we often start with a simple needle stick. In cases in which we are unsuccessful, we might resort to using a larger, blunt tube and a different, slightly more complicated procedure. We perform belly tap after ultrasound whenever possible. Ultrasound allows us to locate small pockets of fluid within the abdomen. In some cases, it might show us that the abdominal wall is so thick that we must use a special technique to gather the fluid.

Rarely, it is impossible to collect abdominal fluid. This is usually because there is very little free fluid in the abdomen. In other cases, clots of inflammatory material or feed can block the needle or tube.

Once the abdominal fluid is collected and visually assessed by the vet, it is analyzed in the lab. Total protein is commonly measured. Total protein in normal abdominal fluid should be very low (less than 1.0 g/dl).

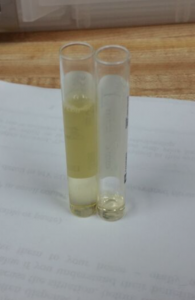

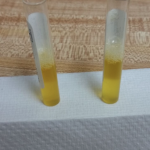

Normal abdominal fluid is clear & usually pale yellow or straw colored.

Cloudy abdominal fluid is indicative of the presence of inflammatory cells.

As intestine is damaged, the blood vessels in the wall become leaky and allow protein to escape and to enter the surrounding fluid. We then see an increase in total protein in the fluid. Total protein over 2.5 can indicate a severe disease process going on in the abdomen. Changes in abdominal fluid characteristics are also useful in determining progression of disease.

Properly performed, the risk of abdominocentesis is very low, although it is slightly higher in foals. The main risk is puncture of intestine, leading to leakage of bacteria-laden intestinal contents, causing inflammation and/or infection of the abdomen.

Reddish-orange cloudy abdominal fluid often indicates intestinal damage.

Great article! My 3 yo just went through a very painful colic that required an overnight visit at the vet clinic. The situation was so tense that I didn’t ask questions as to what the vet was looking for in regards to reflux. This answered all my questions.

Thanks for the comment Elisha, we hope your 3yo lives a long and healthy life! – The HSVG Team