What’s Wrong with Mr. Ed?

As a practitioner of equine veterinary medicine for over 20 years, I believe that it is very important for horse owners to understand the difference between a symptom, an observation, diagnostics, a clinical sign or finding, differential (possible) diagnoses, and treatments. However, in the equine world, these concepts are regularly confused or conflated. This yields false logic that too often results in poor choices, wasted money, and harm to horses.

In creating HSVG, I organized these discrete components into categories in order to clearly define their place within the whole.

A SYMPTOM is perceived and experienced by a patient. It is subjective and cannot be measured. In human medicine (with the exception of pediatrics – infants and young children), patients simply tell their doctor about their symptoms as part of the history and physical exam: “Doctor, my back is very sore and tender right here, and it really hurts when you touch it.” Symptoms include pain (of all kinds), dizziness, anxiety, nausea, chills, fatigue, itching, cramping, and numerous others. Since I have not met Mr. Ed the talking horse, I usually don’t ask a horse about their symptoms – and there are no symptoms in HSVG.

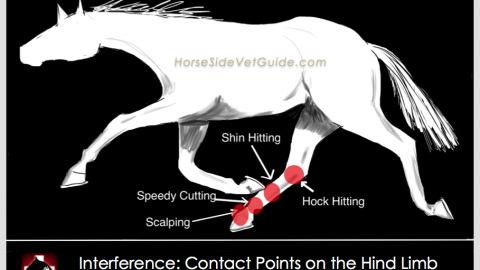

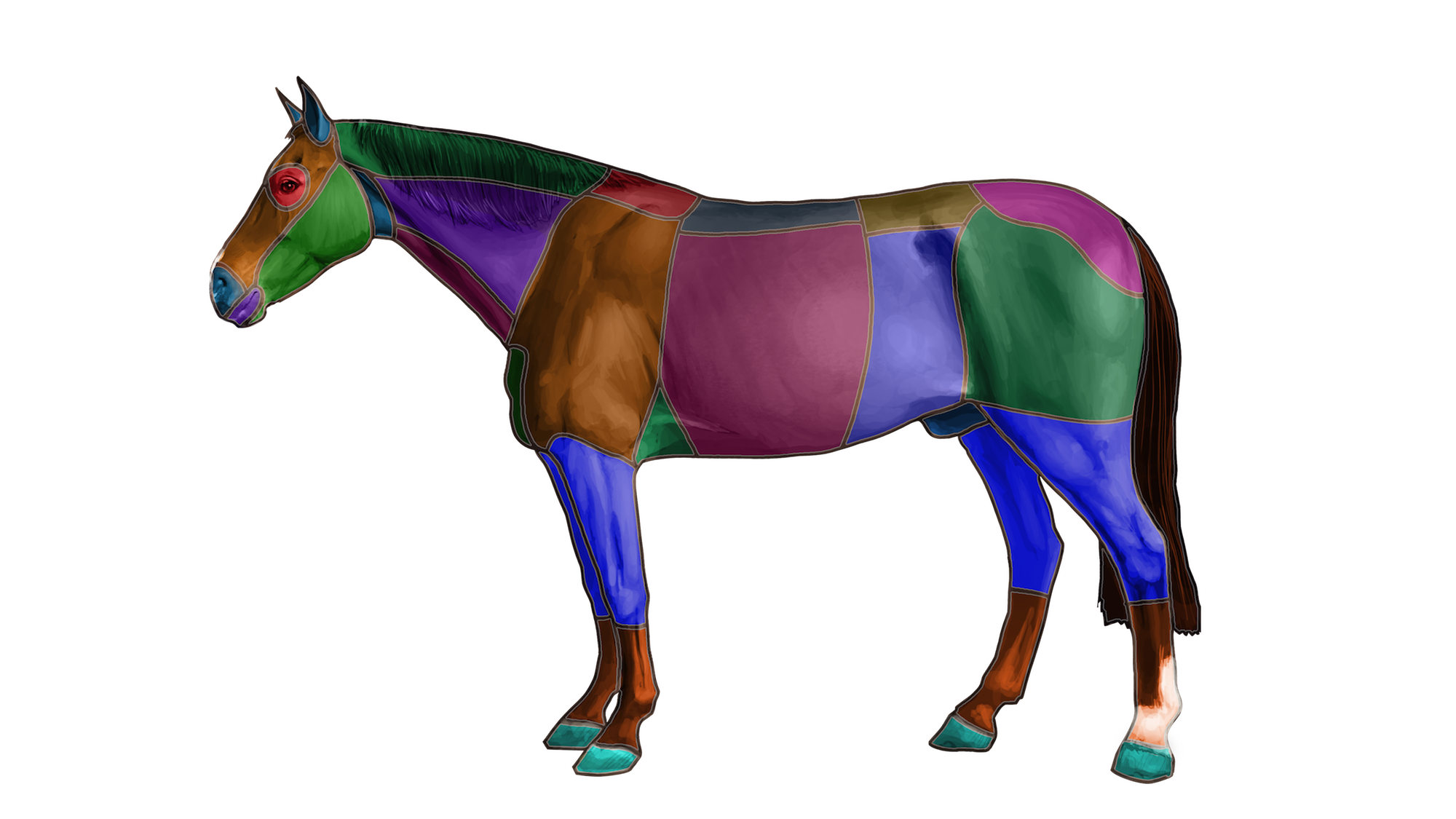

YOUR OBSERVATION is what you perceive or see your horse doing or exhibiting, without jumping to any conclusions about the underlying cause. Since horses cannot talk, they cannot tell you (or me) that they are experiencing back pain. Instead, you may perceive that they dip away from pressure when you try to brush their back, they pin their ears, or they try to kick you when you try to saddle them – all observations.

Observing your horse is an important skill that you can improve upon with practice. The key is in trying to be as objective as possible when you are performing this skill. For example, “I think my horse threw its back out…” – is an assumption or conclusion. Look again for OBSERVATIONS. Perhaps the horse is reluctant to move forward, they grunt or groan when asked to move forward, or their limbs appear rigid or stiff?

A CLINICAL SIGN is an objectively measurable indication of illness, injury, or disease that a veterinarian sees or finds during an initial physical examination or in the performance of comparatively simple diagnostic testing. Examples of a clinical sign include high or low blood pressure, weak pulse, pale gums, and bruising among many others. Sometimes – not always – a clinical sign may be akin to an observation.

A veterinary DIAGNOSTIC is an examination or test that a veterinarian performs to gather more information about a patient’s condition. It might help narrow down the possible causes that result in an observation (or clinical sign) or help rule out diagnoses from a differential DIAGNOSES list.

Veterinary diagnostics range widely in cost and complexity. The value of the information to be gained from a diagnostic may also vary widely – some diagnostics may pinpoint the cause with great accuracy while others may simply help exclude some diagnoses from the list of possibilities. You should discuss the cost and value of any particular diagnostic with your vet.

I personally distinguish between a clinical sign and a clinical finding. A CLINICAL FINDING is a veterinarian’s result or interpretation of a veterinary diagnostic. It is another objectively measurable indication of illness, injury or disease that results from more complex or specialized diagnostic testing. The difference between a clinical sign and a clinical finding is a matter of degree, not kind. However, unlike a clinical sign, a clinical finding is never akin to an observation. (Clinical signs and findings are located in the “backend” of the HSVG database, and are currently not available on mobile.)

A veterinary DIAGNOSIS – the underlying cause of a problem – is determined by a veterinarian after performing veterinary diagnostics and evaluating the results. Sometimes a diagnosis is definitively reached, sometimes not. Once the diagnosis is determined, then appropriate veterinary TREATMENTS are identified and should be discussed with your vet. Just like diagnostics, treatments can range widely in both cost and complexity. Likewise, you should ask your vet how to measure the efficacy of any particular treatment.

For example, “Oh No! My horse is in excruciating pain, he must have broken his leg!” – is a symptom combined with a diagnosis, both of which are assumptions. Instead of speculating or jumping to conclusions, it is best to begin by looking for OBSERVATIONS. Perhaps the horse is non-weight bearing lame, reluctant to move forward, or the affected limb is swollen? Perhaps there is heat and a digital pulse in the hoof wall? By using the proper diagnostics – including a physical exam and discussion with you – your veterinarian may determine that it’s not a fracture at all, but merely a sole abscess.

Unlike veterinary treatments, which are provided by your vet, you can help care for your horse before and after a diagnosis is reached by using your SKILLS & SUPPLIES.

The term “SYMPTOMATIC TREATMENT” applies when a veterinarian treats the symptoms associated with a disease or illness, rather than treating the underlying cause. For example, a horse may be experiencing abdominal pain (a symptom), and outwardly exhibit this pain by pawing, getting up and down, and grinding their teeth (your observations).

A vet may give the horse a shot of Banamine® for temporary pain relief (a symptomatic treatment), and then perform additional diagnostics to determine what is causing the colic (a diagnosis), and then consider appropriate treatments. The shot of Banamine® may help, but it does not simply “fix” the problem or miraculously “cure” the horse. Great care should always be taken when using symptomatic treatments, because they often reduce signs of illness or disease and can easily provide horse owners with false confidence..

Note: The term “symptomatic” is a bit mismatched here. Remember, horses cannot tell you or your vet about the symptoms they are experiencing. Instead, you use your power of observation and your vet uses diagnostics (including their power of observation) to determine what is wrong – reach a diagnosis – choose an appropriate treatment(s), and assess the efficacy of treatment.

I hope this explanation is helpful.

– Douglas O. Thal DVM Dipl. ABVP