Parasite Control: A New Paradigm

Equine parasites are becoming resistant to our deworming compounds. Outdated worming practices (fast rotation of random compounds) are making the problem worse.

In the last ten years, there has been increasing evidence for worm resistance to common de-worming chemicals. If worms develop resistance to our available de-worming medications, we will no longer be able to protect our horses from worm-associated diseases.

Parasite resistance is a serious problem and will require that the whole horse industry change its way of doing things. It is critical that you, as a horse owners or equine professional, understand the nature of the problem, and help solve it.

Some Background

It is natural for healthy horses to have some parasites. Craig Reinemeyer DVM PhD, a renowned expert on equine parasitology states the problem well: “Equine parasites have co-evolved with the horse over 60 million years of evolution. They are unique to the horse, and they can only survive if the horse survives. It doesn’t make sense that to burn down their only home. We need to manage parasites, not eradicate them. Our efforts at eradication are what have led us quickly to resistance.”

As horse owners and caretakers, it is very important that you take a more intelligent approach to parasite control. Simply worming your horses with a rotation of deworming pastes is no longer considered the best approach. Of course, you need to keep parasite numbers managed in your horses. But that need has to be balanced with better methods if we are going to slow the onset of resistance.

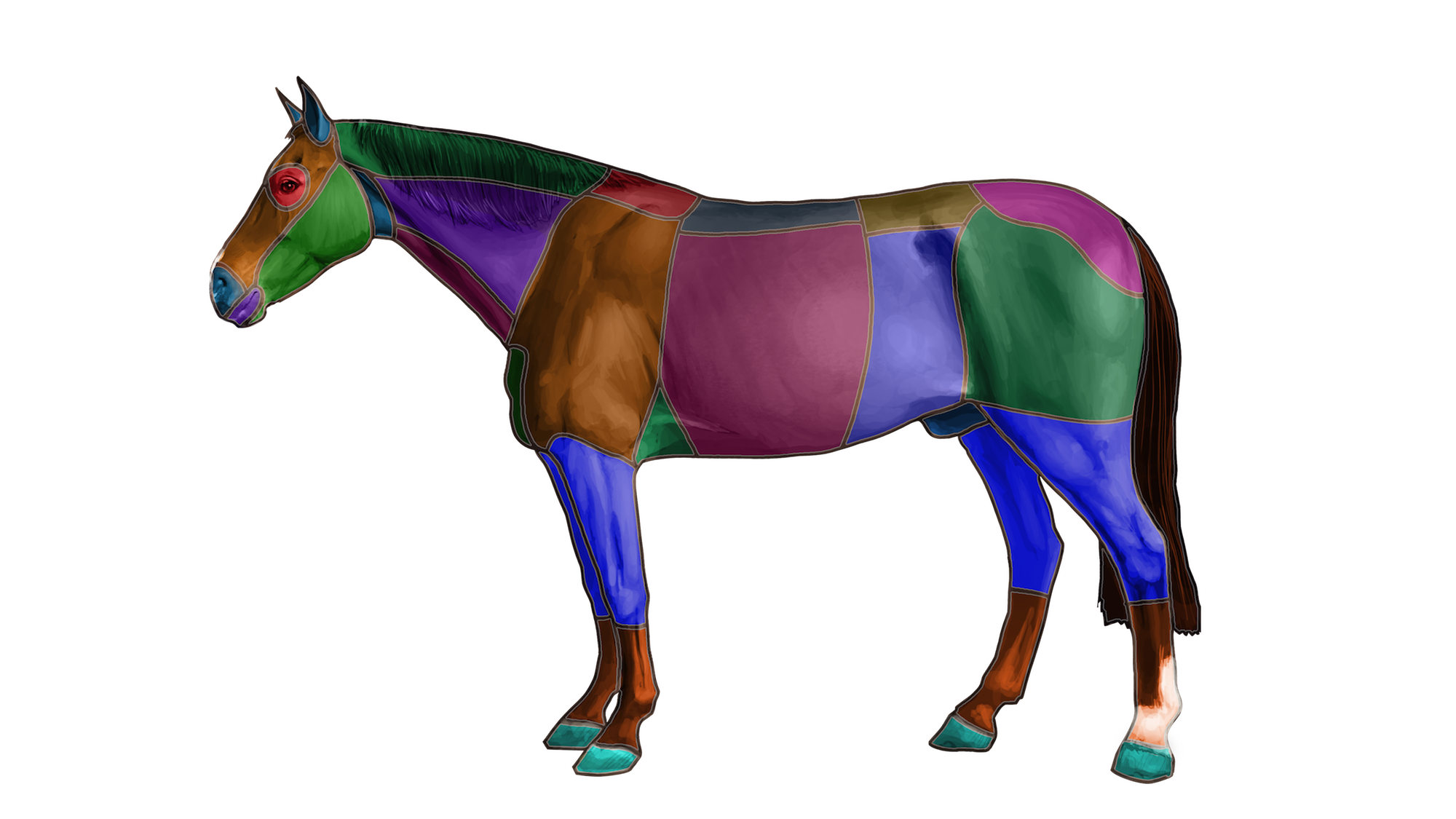

ABOUT THE PARASITES

There are more than 150 species of internal parasites that affect horses. The most important groups include:

-

Ascarids (Roundworms)

-

Large strongyles (Bloodworms)

-

Small Strongyles

-

Pinworms

-

Bots

-

Tapeworms

The Basic Parasite Life Cycle

Internal parasites have a life-cycle that involves stages within the horse and stages in the environment. Parasites released into the environment in manure take time to develop into stages that can be swallowed by the horse, to survive and continue the cycle. The climate must be “right” for this environmental development to take place.

Management to reduce parasites is focused on controlling but not eliminating parasites, with the goal to maintain excellent equine health. To do this, the program must take into account the life cycle of parasite types common to your situation, their life cycles and your geographic region’s climate.

Any one, or all of these parasite types may be present in the horse at one time, and may be at different stages in their life cycles. Some worm species can lay hundreds of thousands of eggs per day, so parasite loads can grow quickly both on pasture and in horses. The different de-wormers have varying effectiveness against the types and stages of parasites. Intelligent control of parasites must take all these factors, and many others into account.

PARASITE DAMAGE

Healthy horses have some parasites, and you would never know it. It’s just the way it is, and it doesn’t hurt the horse.

Horses with parasites can also show a wide variety of signs of illness. The specific signs shown depend upon the specific parasites we are talking about, the horse’s general health and immunity and the population of worms.

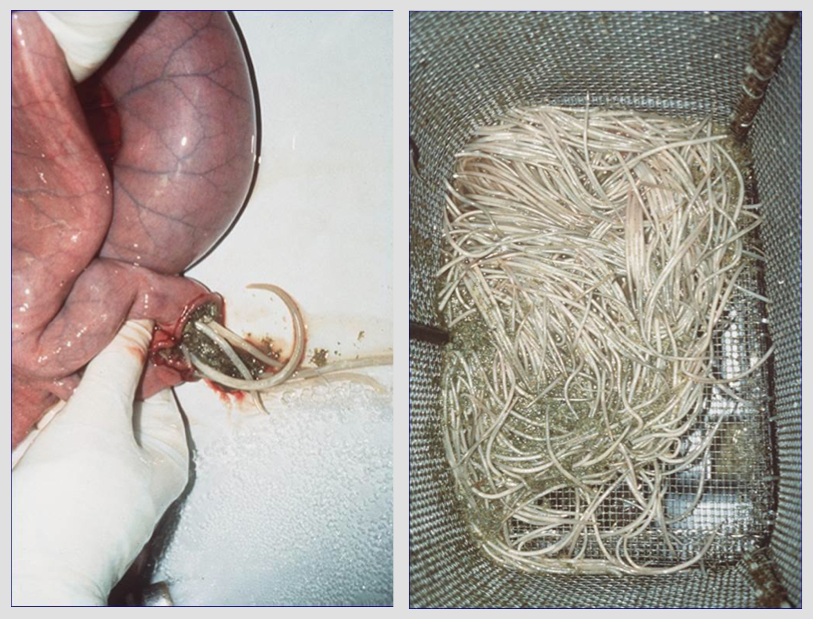

In contrast, HEAVY intestinal parasite loads can cause all sorts of problems for horses, including gastrointestinal irritation and damage, reduced nutrient uptake and generally poor health. Horses affected by large parasite loads look like we would expect them to: pot-bellied, rough coated and thin. They may experience colic, or have diarrhea. But this situation is relatively uncommon in developed countries.

Specific parasites do cause specific conditions, depending upon the organs they affect. Here are some examples, but there are many, many more:

-

Pinworms cause skin irritation and itching to the area around the anus and tail head.

-

Thelazia eye worms cause eye inflammation.

-

Large strongyles can cause life-threatening intestinal damage. The adults of this species localize in the large arteries supplying blood to the intestine. They can result in loss of blood supply to segments of intestine, a potentially fatal problem which results in signs of colic.

-

Bots are not thought to cause much problem at all, although the egg-laying adult flies are highly irritating to horses.

-

The most common species of Tapeworm lives in a specific segment of small intestine, and in large numbers can cause irritation and blockage of the intestine.

-

Lungworms are common in donkeys and cause coughing, usually in horses stabled with donkeys.

-

Large roundworms in young horses (Ascarids), can cause ill thrift and, at times, complete obstruction of the intestine that usually occurs after deworming.

-

Habronema worms transmitted by flies cause non-healing wounds called Summer Sores.

-

Certain parasite stages can damage vital tissues like lungs or liver causing illness related to that organ. This usually occurs as larval stages migrate through the horse’s system to complete their life cycles.

Key Point: Small numbers of intestinal parasites usually don’t cause obvious visible illness in horses. The parasites operate “behind the scenes”. Horses usually look perfectly healthy, or show only very subtle signs. And you wouldn’t expect to see anything in the manure – most parasite eggs and the worms themselves are mostly tiny or microscopic and so are rarely visible in manure.

THE PARADIGM SHIFT

Over the past half-century, deworming compounds have been developed that have drastically reduced parasite problems in horses. “Thrombo-embolic colic” was a common and often fatal condition involving blockage of the blood supply to parts of the intestine. The condition is caused by Strongylus vulgaris, the large Strongyle. This worm has almost been eliminated by the worming campaign of the last 40 years and so this condition is now very rare.

There are far fewer severe parasite-related problems than there were 40 years ago. There have been several main “chemical classes” of dewormers that have been developed over that time. These have drastically reduced the number of parasites in horses. But the cost of this effective campaign has been the development of resistance to these compounds, especially in small Strongyle parasites. This has resulted in the growing ineffectiveness of these drugs. Recently, researchers have shown that this resistance is a greater problem than we thought, and that it is progressing rapidly. We are beginning to see resistance to even our newest and most potent chemical class.

Before the advent of paste dewormers, veterinarians were very involved in equine parasite control. Veterinarians typically tube-wormed horses, meaning that they passed a stomach tube and dosed a large quantity of the chosen chemical directly into the stomach. In the last 25 years, paste formulations of the common chemical classes have become increasingly available and very cheap. Horse owners have rotated dewormers casually, not understanding the problem, and under the false assumption that “more is better”. Veterinarians, including myself, were complicit in this approach. Ten years ago, I consistently recommended a fast rotation program to my clients without understanding the potential implications.

We now need to completely re-think how we deworm our horses. Misconception and lack of awareness by the whole industry has led to the development of a very large problem.

THE PROBLEM WITH THE OLD PARADIGM

Fecal egg counts involve microscopic examination of manure for quantifying the number of parasite eggs of different types. We have learned certain things about equine parasites from doing fecal egg counts. We know we can make the worms disappear from the manure by using deworming compounds. We assumed that if we rotated compounds, that parasites that were not killed by one class, would be killed by the next. This idea worked well when the 3 main chemical classes each killed the majority of parasites. However, this is becoming less and less true.

KEY POINTS:

-

Two out of the three main classes of chemical no longer kill parasites adequately. Parasites have become resistant to them. Their continued indiscriminate use will quickly result in complete resistance.

-

Rotation using ineffective compounds ensures complete resistance to them while creating a false sense of security. The potency of the effective dewormers “covers up” the inadequacy of the others in the rotation.

-

We are already seeing pockets of resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin (our last remaining effective class) and it is inevitable that this will increase. Use of these compounds without fecal testing will ensure a short effective life for them.

-

There are no new chemical compounds in the works right now. Research and development is costly and takes time. Our emphasis should be on extending the effectiveness of the drugs we have.

UNDERSTANDING PARASITE RESISTANCE

Parasites develop resistance to the chemicals used to kill them. Resistance is based on individual worm genetics and selection for these genetic traits, i.e. natural selection. Most parasites are killed by a properly administered and effective dewormer application. Out of thousands of worms in the horse, most will be killed, but there may be a few surviving (resistant) parasites that have genetic differences that allow them to tolerate the chemical.

These few survivors can then occasionally interbreed with other similarly resistant parasites, leading to a higher number of resistant parasites in the next generation. These offspring survive and propagate, resulting in the next generation being comprised of even more resistant parasites. You won’t see this process taking place. It all happens behind the scenes.

The greater the percentage of the worm population that is exposed to a compound, the greater the pressure for the parasite populations to develop resistance against it, and the faster the percentage of parasites becomes the new, resistant type. Indiscriminate de-wormer use has and will accelerate the onset of this resistance. It is inevitable that this process will take place with enough time and exposure to these compounds. Our goal should be to make that period as long as possible for each of our de-wormers. How do we achieve this? By MINIMIZING the exposure to these compounds through only “targeted” deworming.

LIMITED DEWORMING & INCREASED FECAL SAMPLE TESTING

The best way to prevent development of resistance to these compounds is not to use them at all! That would surely and completely eliminate any selective advantage to resistance. Obviously this is not feasible because our horses would again succumb to the effects of parasites. However, leaving a SEGMENT of the parasite population with minimal exposure to these chemicals WILL slow the onset of resistance. Those susceptible parasites are allowed to go on living and competing with the resistant parasites. This is known as preserving “refugia” within the worm population.

We can move toward this concept by only deworming horses that have higher fecal egg counts. For horses with lower counts, we drastically reduce the number of deworming treatments per year.

Determining “who gets what” requires an understanding of which horses have higher worm burdens and shed more into the environment. This knowledge requires fecal testing.

HOW IT’S DONE – FECAL EGG COUNTS

Fecal Egg Counts (Fecal Exams) are the cornerstone of targeted deworming. Here is how they work: Worm eggs are shed in the manure. Most worm egg types can be identified and counted using a microscope. Accurate testing requires knowledge of the technique, and practice. There are limitations to FEC, as some species are difficult to diagnose this way. Sometimes, eggs may only be shed intermittently, meaning that they can be missed. Regardless, FEC is the best indicator we have of worm burden in horses.

By using fecal egg count results, horses are broken into 3 groups, those with high parasite burden and shedding into the environment, those with moderate, and those with minimal. Only those in group 1 are dewormed frequently, about 3 times per year. The others are dewormed less. The goals of this new approach are optimal horse health for all horses in the herd, reduced dependency on chemicals and reduced contribution to the resistance problem, and improved fecal diagnostics to monitor the effectiveness of the program.

The key to this new approach to deworming is working with your veterinarian. There is no perfect de-wormer and no standard program. Fecal testing guides the program. Horses at different ages and stages have varying needs for parasite control. Twenty percent of horses in a group shed 80% of the total parasites. Young, growing horses have some special needs. Young foals are especially susceptible to ascarid (roundworm) infestation, and may benefit from deworming with an appropriate compound at 30-60 day intervals until they build some natural resistance.

Climatic conditions and season of year influence parasite levels in the horse and on pasture and are critical factors to address. The goal is not to kill ALL parasites, but to keep parasite loads to a level compatible with health, and to leave a reservoir (refugia) of parasites in as many horses as is practical.

Based on this new paradigm, in our veterinary practice we recommend a fecal exam on every horse twice annually, in our area in May and October. Testing is the only way to determine the effectiveness of a parasite control program and to detect the development of resistant parasites.

It’s important to know that there are limitations to fecal egg counts. Certain types of parasite eggs can be missed using typical lab methods. Eggs are not continuously shed by the horse either. So it’s possible that a particular fecal ball may not contain eggs, but the parasites are still in the horse.

YOUR ROLE

-

Collecting a fecal sample is easy. Simply pick up 1 fresh fecal ball in a zip lock bag, squeeze the air out of the bag, label it with your horse’s name, and drop it by your veterinarian’s office. You can store a fresh sample up to 12 hours if you keep it refrigerated. At our clinic, we do this testing in-house. We provide our clients with the results within 24 hours.

-

It is important that the sample be taken at least 3 months after deworming, and 4 months after deworming with a Quest compound. Otherwise the effect from the prior deworming confuses the results.

-

If horses are on a continuous dewormer like Strongid C, they can be tested at any time.

YOUR VETERINARIAN’S ROLE

-

Your vet assesses your overall program. This includes the susceptibility of your horses, management, your geographic region and environment. They help you tailor your program to these factors and to the results of Fecal Egg Counts.

-

They perform a fecal egg count on your samples and determine which horses are low (< 200 epg), moderate (200-500 epg) or heavy (>500 epg) shedders.

-

They identify the specific parasite species, allowing a determination to be made of the most effective deworming compound. You will then deworm the horses with the appropriate compound.

-

Once annually at least, they will perform a FECRT (Fecal Egg count reduction test). To do this, you submit a second sample two weeks after deworming. The veterinarian performs another fecal egg count on that sample. If the drugs are working the way they should, there should be almost no parasite eggs in the second sample.

-

A customized approach for worming is then tailored to the situation. Horses are dewormed with the appropriate compound based on their category. Low shedders are dewormed once or twice annually, spring and fall. Moderate shedders are dewormed three times annually. Heavy shedders are dewormed up to 4 times annually.

-

The cost of fecal testing should be offset by a significant savings in the purchase of deworming compounds.

DEWORMING COMPOUNDS

It is vital for you to understand that there is a big difference between trade names and active ingredients. Currently-used deworming compounds can be divided into three basic groups effective against worms other than tapeworms and one compound specific to tapeworms:

-

Benzimidazole Products. The oldest class and that with the highest resistance in small strongyles. Examples include Oxibendazole (Anthelcide EQ) Fenbendazole (Panacur, SafeGuard). Still the best wormer class for use in young horses- is our most effective compound against Ascarids, the main parasite of young horses.

-

Pyrantel Products. Less resistance, but still a rapidly-growing problem. Trade names include Strongid paste, Strongid C, Rotectrin 2. Pyrantel has some effect against Tapeworms but is not as effective as praziquantel. This drug can be used on a limited basis, with FECR tests.

-

Ivermectin/ Moxidectin. Two related compounds. We are seeing the beginnings of resistance problems to this class, but these are still very effective against a wide variety of parasites. Both products kill bots in the stomach. Moxidectin is the newest deworming compound, has the fewest resistance problems, and kills encysted small strongyles. There is strong resistance to this class of wormer now being seen in Ascarids. For this reason, this class of drugs should probably be used very little in horses under 1 year of age.

-

Praziquantel. This compound is effective only for Tapeworms, which are not killed by the other compounds. In several commercial products, Praziquantel is added to one of the others to kill tapeworms. Much of the USA probably does not have a problem with Tapeworms. So care needs to be taken not to overuse these products.

METHODS OF DELIVERY

PASTE – Oral paste syringe or liquid is the most common method of de-wormer delivery. Deworming pastes and feed formulations have been the foundation of deworming programs because of convenience, cost and ease of administration.

TUBE DEWORMING – Prior to the development of Ivermectin in the early 1980’s, tube deworming was the standard method for parasite control. Tube worming is performed by a veterinarian using a rubber naso-gastric tube. The technique still has its place and is highly effective because it allows a large dose of chemical to be delivered into the stomach at once. There is minimal temporary discomfort for the horse as the tube is passed through the nostril and down the esophagus into the stomach. Because of the skill required, this procedure should be performed only by a veterinarian.

SUPPLEMENT – Daily deworming with a feed supplement. The most common continuous dewormer is Strongid C®. Continuous dewormers like Strongid C® (pyrantel) are still frequently used and tend to be highly effective in decreasing worm loads in horses and on pasture. They work by inhibiting the larval stages of many worm species. Horses on a continuous wormer should still be dewormed with either Ivermectin or Moxidectin Praziquantel in the spring and late fall. This is primarily to kill bots and tapeworms not affected by the Strongid C®. Horses on Strongid C® should have fecal testing performed 1-2 times per year to assess the effectiveness of the program. Horses have FEC’s performed while they are on this supplement.

In a recent discussion with Dr. Reinemeyer, regarding the place of continuous worming regimens he said: “Continuous wormers still have a place. They can be given to select horses within a group for which we want minimal worm burden (say a show horse being pastured with riding horses). But we should never give it to all the horses in a herd, and we should stick to just short term- never for the life of the horse.”

All three methods of delivery are effective and likely have their place in the new paradigm. The key is that the deworming product must be given to the proper horses, in the proper dose, at the proper time. Decisions must be guided by testing. Administration must be such that the animal actually ingests the required dose.

ADDITIONAL POINTS TO CONSIDER

-

Any deworming today should be based on a discussion with your vet and results of fecal testing.

-

Some horses are considered “difficult to deworm”. The fact is that any halter-trained equine can be taught to easily accept paste medication, if the RIGHT TECHNIQUE is used.

-

It is critical to get the correct dose to the stomach. Under-dosing is ineffective and contributes to parasite resistance. It is best to err on the side of a slight overdose, with all compounds except Quest (moxidectin) products, which are less safe at higher doses.

-

For moxidection-containing products (Quest), the dose must be calculated based on the horse’s weight, as overdose is possible. Overdose is unlikely with the other products. While moxidectin products are very effective, I do not recommend them for horses less than 2 years or under 600 lbs. I personally do not use these products in pregnant mares either, although they are likely safe.

-

Some horses may find pastes unpalatable and try to spit them out. It is best to dose before feeding because horses with feed in their mouths can more easily spit out the paste.

-

Products with Praziquantel are available and have excellent effectiveness against tapeworms and should be used as directed. Your vet can tell you whether they are indicated in your area.

-

Diatomaceous Earth and other “natural” wormers. Unfortunately, the research suggests that diatomaceous earth does not work. Hopefully, in the future there will be some progress here. There are worm killing fungi and now even a worm killing bacteria that are reported to be effective treatments. For now, until your vet recommends these products, your best bet is not to rely on them, no matter the claims that are made by those selling them.

-

Remove bot eggs regularly from the horse’s hair coat to prevent ingestion. Bots generally do not cause serious disease but if they can be removed it means fewer will be ingested.

-

Foals should not be dewormed until they have adult ascarids present- at least 60-70 days. On average, they should be dewormed every 3 months thereafter until they are a year old, with a compound that kills ascarids (oxibendazole or fenbendazole). After that, they are monitored with fecal egg counts and treated as adults. Foals that appear poor can have fecal egg counts performed and may require a different approach.

-

Pregnant mares should be dewormed with a safe product a few weeks prior to foaling to decrease the foal’s exposure to parasites, unless they are ill or have complicated pregnancies.

-

There is a strong argument that continuous wormers like Strongid C are contributing to the problem with pyrantel resistance, and some believe its use should be discontinued.

PASTURE & STABLE MANAGEMENT

Importantly, chemical control is actually the less important part of a total parasite control plan. Since parasites are primarily transferred through manure, good stable and pasture management is key.

-

Pick up and dispose of manure from stabled horses on a frequent basis.

-

Horses in growing pastures tend to defecate in certain areas in the pasture (the roughs) and graze in between these (the greens). This is likely an adaptive behavior reducing ingestion of parasite eggs. Keep this in mind given your management of the pasture.

-

When possible, use a feeder for hay and grain rather than feeding on the ground.

-

Harrowing pastures regularly may break up manure piles and expose parasite eggs and larvae to the elements, but also spreads viable eggs out onto the grass so that horses are forced to ingest more parasites. My recommendation in our area is to only harrow horse pasture when the weather is hot and dry during the peak of the summer, then to allow several weeks for the parasites to die before putting horses out.

-

While eggs may be slow to develop to infective stages in cold weather, they do survive, awaiting the right conditions. Many parasite eggs survive on snow and ice for the winter and may resume their life cycle in the spring. The old idea that cold weather kills parasites is mostly wrong.

-

Spreading manure on pastures without first composting it will spread parasite eggs on the pasture and can lead to heavy pasture contamination and re-infestation.

-

Composting requires watering (in our climate) and turning of piles. Properly done, this leads to intense heat production and killing of most parasites. With proper management, composted manure can be returned to the land and benefit it.

-

Rotate pastures by allowing other livestock, such as sheep or cattle to graze them. This interrupts the life cycles of equine parasites.

-

Group horses by age to reduce exposure to certain parasites and maximize the deworming program geared to that group.

-

Keep the number of horses per acre to a minimum to prevent overgrazing and reduce the fecal contamination per acre, or use rotational grazing.

Love the article! I regularly worm my horse for all the common types of parasites. However, three years ago my mare caught West Nile Virus and this was a very traumatic time. This is such a big problem which i think needs more attention. My best friend who is a local vet wrote an article for Horses Mad (http://www.horsesmad.com/west-nile-virus-horses/) and brilliantly covers the issue. Parasites can be deadly for your horse, so please remember to worm and vaccinate them regularly!

Interesting and helpful article – and great app by the way!

My vet told me to start fecal testing my horses instead of rotational deworming about 2 years ago. I did not really understand why and the article above is very helpful. Now I get it. Funny how our historic response to the worms has created super worms!

very useful information thank you for sharing it.

My vet tube worms with a tube down the nose into tummy the we use s tube paste that gets tapes